Currently Sailing in Erie, Pennsylvania, in Collaboration with Flagship Niagara League

A National Historic Landmark, the Seaport Museum’s 1893 schooner Lettie G. Howard is one of few surviving examples of Fredonia type fishing schooners once in wide use in the North Atlantic and typical of those that once called at the Fulton Fish Market. She is a rare beauty with classic fishing schooner lines, turning heads wherever she goes. After an active life in the fisheries of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, Lettie G. Howard arrived at South Street Seaport Museum in 1968.

Since 2018, Lettie G. Howard has been operating with a partner organization, the Flagship Niagara League in Erie, Pennsylvania, providing sailing tours and delivering enriching programming to the Erie community, school groups, visitors, and volunteers. The Seaport Museum eagerly anticipates flying the South Street Seaport Museum flag aboard Lettie in the region this season.

Fredonia Fishing Schooners

Lettie G. Howard was included in the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and designated National Historic Landmark in 1989, based on her identity as the sole surviving inshore model of a Fredonia type fishing schooner. These Essex and Gloucester-built vessels, like their predecessors and followers, were largely mass produced by the regional shipyards employing journeymen shipwrights, caulkers, and riggers. Ordered by Captain Fred Howard from Beverly, Massachusetts, in honor of his daughter Lettie Gould Howard’s 22nd birthday, Lettie was built at the Arthur D. Story yard in Essex, Massachusetts.

View of Gloucester Harbor, ca. 1890-1915. Silver gelatin dry plate negative. Thomas W. Kennedy Collection 2016.003.0080

Fishing in the Atlantic has always been a hazardous profession and remains so today. In the period from 1866 and 1890, the town of Gloucester lost 382 schooners and 2,454 fishermen. The Fredonia schooner came into existence largely as a result of efforts to end this heavy loss of life and property. In 1882, Joseph W. Collins (1939–1904), a former schooner captain employed by the U.S. Fish Commission, wrote a series of letters to a Gloucester paper condemning the design of vessels. He was particularly critical of the shallow draft that made the boats capsize easily when caught by a sudden gust of wind or “tripped” by a large wave. Collins advocated for deeper hulls and sharper lines for sailing to windward. The sharper lines would also give the schooners more speed, enabling them to get the catch to port sooner and make more trips.

Collins challenged designers to solve the problem and, in 1887, collaborated with Boston-based Canadian-Irish shipbuilder and yacht designer Dennison J. Lawlor (1824–1892) to produce the schooner Grampus for the Fish Commission. Edward Burgess (1848–1891), the Boston-based yacht designer renowned for crafting three successful America’s Cup yachts from 1885 to 1887, also took up the challenge. His first fishing schooner was the Carrie E. Phillips of 1887, launched by Arthur D. Story shipyard (active 1832–1932) in Essex, Massachusetts, which would go on to build Lettie G. Howard six years later. In 1889, the schooners Nellie Dixon and Fredonia were built from an even more revolutionary Burgess design. They were the forerunners of the type of fishing schooner that would be built for the remaining years of the 19th century, deriving its popular name from the latter vessel.

The defining qualities of the Fredonia type schooner include her rig, clipper bow with gammon knee and billet, and deeper keels aft that rise steeply to shallow forefoots. Their slender hulls, sharp lines, and graceful bows made the schooners almost yacht-like.

When Burgess died in 1891, his design was already widely copied. His major successor was George Melville McClain, who in 1890 produced lines for the Fredonia model Lottie S. Haskins, which became the blueprint for at least eight other schooners, including Lettie G. Howard.

Fulton Fish Market and Commercial Fishing in New York waters

Early fishing was done with handlines on the decks of fishing vessels, “jigging” hooks attached to lead weights off the bottoms. In the mid-1800s, fishing from dories was introduced. However, due to the conditions of the Atlantic Ocean, fishing primarily continued from the deck of the schooner, with one or two dories mainly serving as lifeboats.

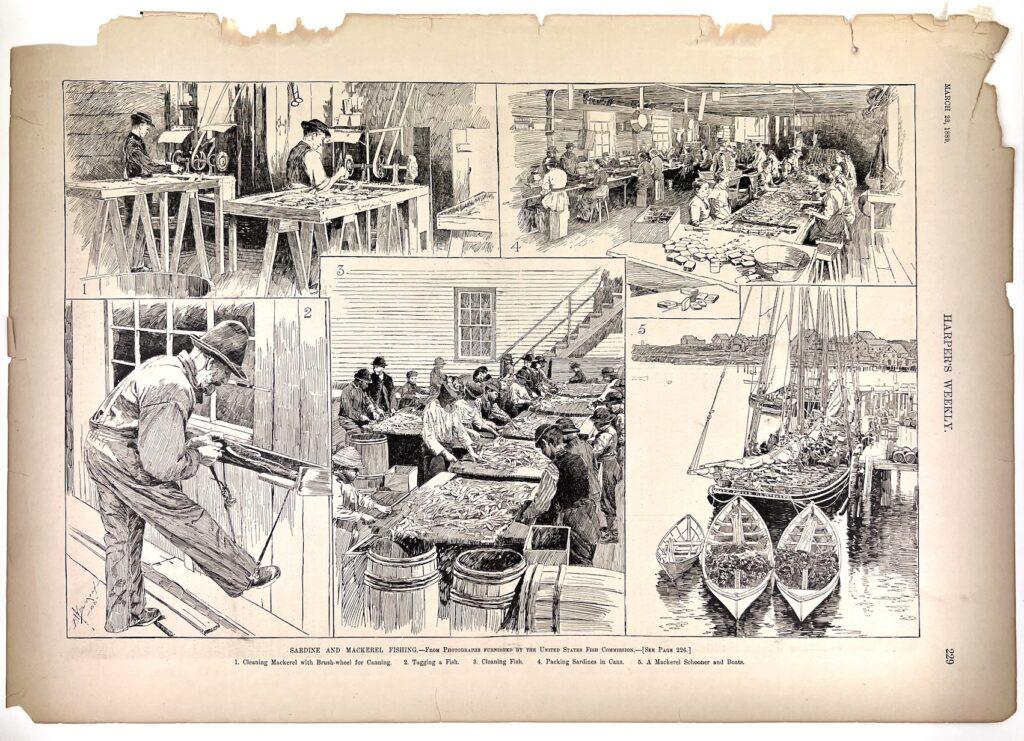

Sardine and Mackerel Fishing, March 23, 1889. Newspaper Clipping Collection 1984.009.0003

Gloucester schooners often followed the fish, working grounds from Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras and landing their catch in nearby ports, including New York. As yet, there is no evidence that Lettie G. Howard brought fish into Manhattan’s Fulton Fish Market, though sister vessels certainly did.

Gulf of Mexico Years

In 1900 the Fishing Gazette reported that representatives of the Mobile Fish and Oyster Company were in Massachusetts to purchase schooners for use in the Gulf of Mexico. Lettie G. Howard is first mentioned in the Pensacola Daily Paper in mid-December 1901, as of the two “smacks” recently bought by E. E. Saunders & Co.[1]When Lettie G. Howard was bought for the snapper fishery, it was by the largest firm in the business. E. E. Saunders & Co. has been founded in 1883 by Thomas E. Welles and Eugene E. Saunders. … Continue reading. By mid-March 1902, the paper was reporting the schooner’s return from the fishing bank with 2,500 red snappers.

The red snapper fishery in the Gulf was established in the early 1850s by captains from New London, Connecticut. They arrived in small sloops they originally used for catching cod off Nantucket. Initially, fishing took place in the northern Gulf, just off the coasts of Florida and Alabama. After the Civil War, schooners were brought down from New England and fishing moved farther south in the Gulf, where Pensacola, Florida rapidly grew to become the center of the fishery.

The Gulf’s schooners provided a cleaner living and working environment due to the absence of salt and the practice of not processing fish on board the ships. The Gulf fishing vessels were often owned by large companies rather than individuals. But these schooners also needed more maintenance than those operating in the northern waters. The Gulf’s most dreaded enemies were hurricanes and the teredo, a boring worm that could quickly riddle any exposed bottom plank. The hulls of boats were protected by coating of copper paint, which was re-applied during dry-docking.

New Identities

Northern-built schooners continued to dominate the snapper fleet well into the 20th century. But all of them, after they spent around 20 years in the fishery, were generally hauled out and thoroughly rebuilt, often acquiring new names and documentation in the process.

In 1923 it was Lettie G. Howard’s turn. Mr. H.L. Mertyns, who operated the marine railway that moved the ship to shipyard, told the Seaport Museum years later that as a “rule of thumb,” 50% of the vessel was replaced to acquire a new identity. Lettie G. Howard was renamed Mystic C in honor of the birthplace of Thomas E. Welles, co-founder of E.E. Saunders & Co., and was back in the red snapper fleet by 1924 with a new gasoline engine[2]It was replaced by a diesel engine in 1947..

As a result of depletion of the fish and foreign competition, the Pensacola red snapper fishery came to an end in the 1960s, and Mystic C was the penultimate vessel sold by E.E. Saunders & Co. in May 1967.

Her buyers were Historic Ship Associates, a small Boston-based group wanting to install a fishing schooner as a tourist attraction on the waterfront of Gloucester. In preparation for this new role, the schooner was restored. Work included adding a main mast, removing the engine, reinstating the type of fish bins originally used in salting down fish in the hold, and cutting doors in bulkheads so that visitors could walk through the vessel’s interior from bow to stern.

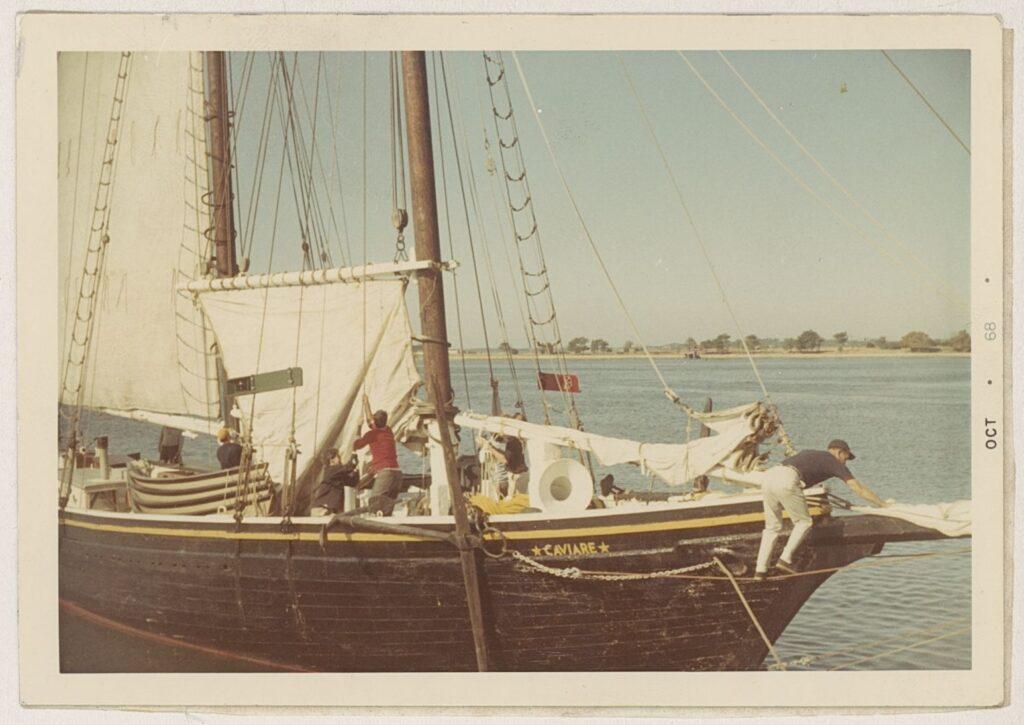

Caviare in Gloucester, September 1968. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

Someone in Pensacola told the Historic Ship Associates that Mystic C was rebuilt from another schooner, the Caviare. A sailmaker’s ledger was then produced with “Caviare” written in at the far left of a page dated 1931. On this basis, the associates renamed the vessel Caviare on June 12, 1967. The attempt to operate the vessel in Gloucester was unsuccessful and the association notified South Street Seaport Museum’s founding President Peter Stanford (1927–2016) that the vessel was available for purchase.

Caviare in Gloucester, October 1968. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

At that time, the Seaport Museum had been seeking a fishing schooner or a cargo-carrying coastal schooner for its proposed fleet of historic vessels. Caviare fit the bill very nicely due to her apparent age and the fact that vessels of her type comprised much of the fleet that called the adjacent Fulton Fish Market at the turn of the 20th century.

Even before Caviare was purchased in September of 1968, Stanford had doubts about her identity. After some research, it was discovered that she was indeed Lettie G. Howard, and all the evidence seemed to fall into place. Lettie was the second historic ship to become part of the Museum’s fleet after LV 87/WAL-512, lightship Ambrose.

Restorations

The Museum acquired the fishing schooner with the intention to sail her on a regular basis. However, less than one month after she arrived, the Museum’s insurers advised that she won’t be able to sail but “only towed by tugs within the harbor limits, and only at time when Coast Guard storm watch or small craft signals are not in effect.”

While docked at the Seaport Museum’s Pier 16 for the next 20 years, Lettie G. Howard was visited by thousands of people who explored her decks. While visitors looked into her fishing bins and narrow crew berths, they gained a sense of what it was like to live and work on a small fishing schooner in the late 19th century.

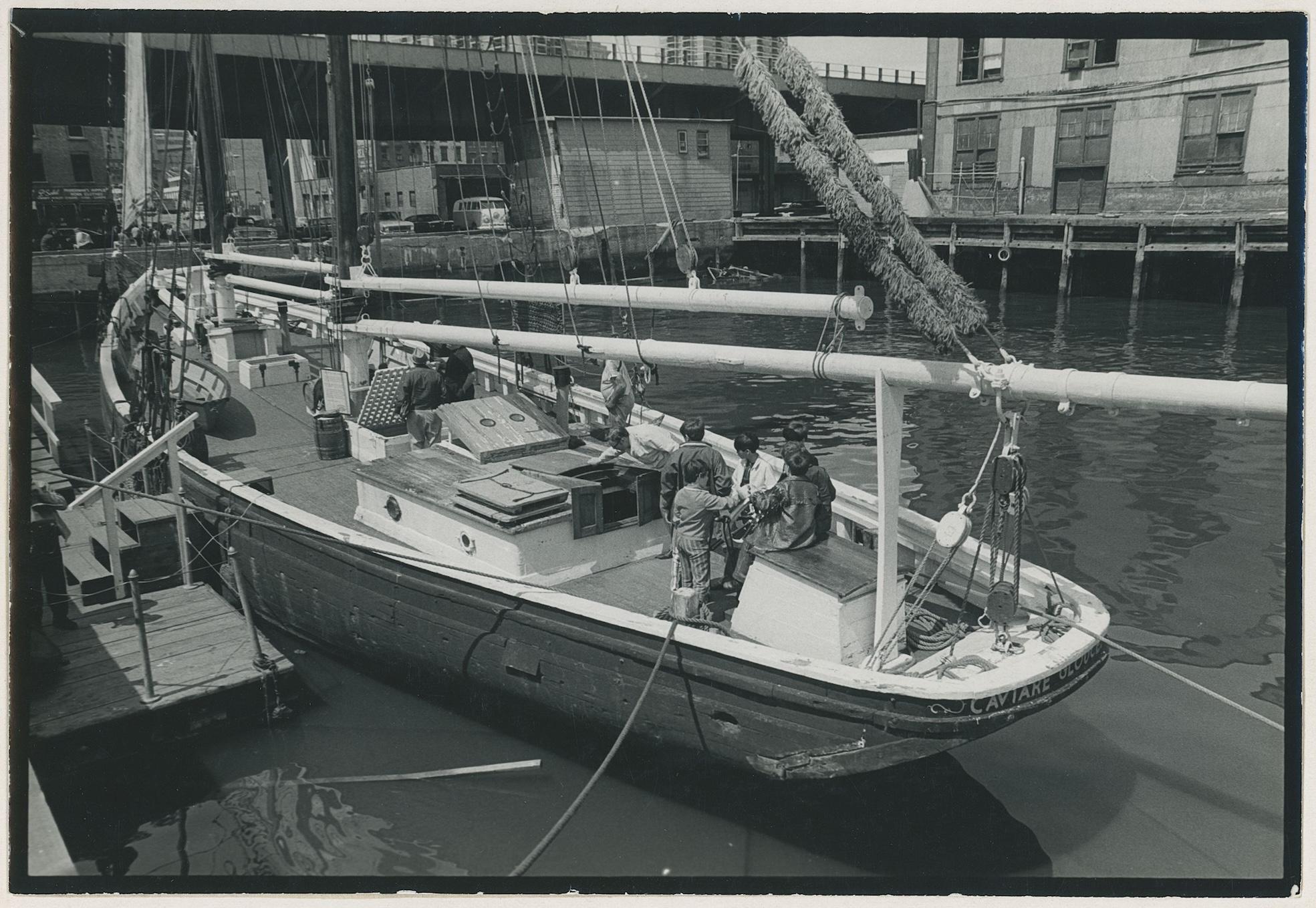

Caviare at Pier 16, ca. 1973. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

Lettie G. Howard was documented in 1989 as part of her National Historic Landmark designation in the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), which documents historically significant engineering, industrial, and maritime works in the U.S. The project is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. HAER high resolution drawings and photographs are on the Library of Congress web site.

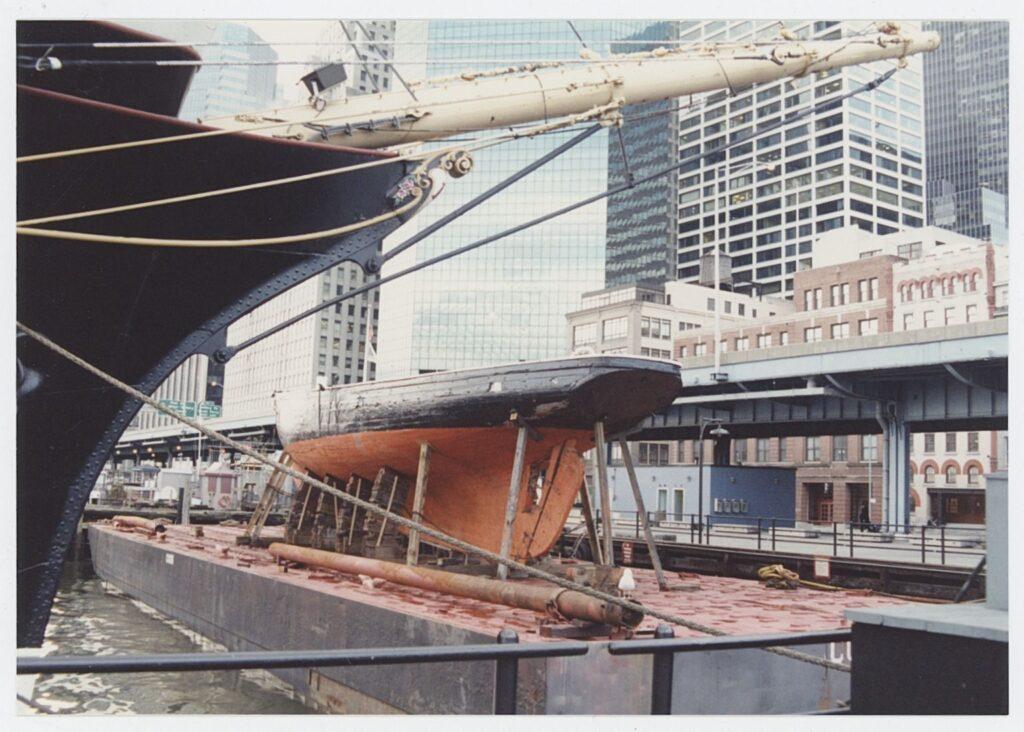

Lettie G. Howard restoration, 1991-1993. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

In 1994, after an extensive two-year rebuild that restored the vessel to her original appearance, she was certified as a Sailing School Vessel by the U.S. Coast Guard and finally began a new career carrying students of all ages on life-changing voyages.

In 2013, in celebration of her 120th birthday and with an eye to the future of this living artifact, South Street Seaport Museum undertook a capital campaign to raise funds for critical repairs and restoration. This project brought Lettie back into service as a Sailing School Vessel, and working in collaboration with New York Harbor School, it ensured her place in the lives of generations of student-sailors to come.

Left: Lettie G. Howard sailing in Gloucester, 2016. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

Right: Lettie G. Howard’s trainees from the New York Harbor School, 2014. South Street Seaport Museum Archive

Since 2018, Lettie G. Howard has been sailing the waters of Lake Erie with a partner organization, the Flagship Niagara League, where she provides sailing tours and delivers enriching programming to the Erie community, school groups, visitors, and volunteers.

Additional readings on Fredonia style fishing schooners and the Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper Fishery

“Baseline of the Gulf of Mexico Red Snapper Fishery 1874-1986” Southeast Fisheries Science Center (SEFSC), 2024.

“The Gloucester Guide: A Stroll Through Place and Time” by Joseph E. Garland, 2018.

“A History of Red Snapper Management in the Gulf of Mexico” by Peter B. Hood, Andrew J.Strelcheck, and Phil Steele. NOAA Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, 2007.

“Down to the Sea: The Fishing Schooners of Gloucester” by Joseph E. Garland, 2000.

“Adventure: Last of the Great Gloucester Dory-fishing Schooners” by Joseph E. Garland with Captain Jim Sharp, 1985.

“Lone Voyager” by Joseph E. Garland, 1963.

Ready for more?

Head over to our Programs and Events page to see what else is happening at the Museum. Sign up for an upcoming talk, learn more about visiting Wavertree, or explore our virtual offerings.

References

| ↑1 | When Lettie G. Howard was bought for the snapper fishery, it was by the largest firm in the business. E. E. Saunders & Co. has been founded in 1883 by Thomas E. Welles and Eugene E. Saunders. Welles was born in Mystic, Connecticut, in 1855 and arrived in Pensacola in 1878. Saunders was born at Narraganset Pier, Rhode Island in 1845, and was a captain of coastal schooners before he successfully established a tugboat fleet in Pensacola. “Seaport” magazine, Winter/Spring 1990, p. 22-23. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It was replaced by a diesel engine in 1947. |